#2 - Three Nonprofit Misconceptions Risk Our Economic Future

As AI eliminates millions of jobs, 501(c)(3) may become the most important organizational technology in human history—if we can see past the charity illusion

How many United States tax code designations do you know off the top of your head? For most people, the answer might be two—401(k) and 501(c)(3).

The first one makes sense because of the direct impact retirement savings have on millions of families across the country, but the second one is more interesting. Most people do not own or run a nonprofit organization, and yet this bureaucratic legal reference number has become synonymous with the term nonprofit, itself, and is nearly as widely known.

But as artificial intelligence eliminates millions of jobs over the next few years, this bureaucratic classification may become the most important organizational technology in human history. Here's why most people fundamentally misunderstand what nonprofits actually are—and why that misconception could cost us our economic future.

Nonprofits are More Than a Tax Designation

In fact, the 501(c)(3) tax designation is only 71 years old and traces back to the Internal Revenue Code of 1954, enacted by Congress through H.R. 8300 and signed into law on August 16, 1954. Does that mean nonprofits are only 71 years old? They’re much older than that.

Prior to 1954, federal taxation derived its authority from the Revenue Act of 1913, which allowed for tax exemption but resulted in a patchwork of qualifications for a number of different kinds of charitable, religious, and educational organizations. The 1954 Act was primarily an administrative maneuver to consolidate, simplify and clarify.

Congress wanted to gather all the scattered tax-exempt provisions into one system, establish a unified numbering schema from 501(c)(1) to (c)(29), and define more precisely what these organizations could, and could not do under each designation.

Before 1913, there had been no permanent federal income tax and, therefore, no need for tax exemption. However, beginning in 1862 during the Civil War when the first temporary federal income tax was implemented to fund the war effort, there had been several attempts to establish standard federalized taxation, which were debated in court until the 1913 passage of 16th Amendment to the United States Constitution gave Congress the authority to levy an income tax without apportioning it among the states on the basis of population.

The truth about nonprofits, or purpose-driven organizations, is they predate even the founding of the United States. Harvard University, established in 1636 as Harvard College, was founded "to advance learning and perpetuate it to posterity." Yale followed in 1701. The University of Pennsylvania, also founded by Benjamin Franklin, opened in 1740. These institutions trained the Founding Fathers, developed the intellectual frameworks for democracy, and created America's early leadership class.

One of this country’s first purpose driven organizations was the Library Company of Philadelphia, which was started by Benjamin Franklin in 1731.

He founded it on a radically simple insight: a group of individuals could pool resources to create something beneficial that none could afford alone. Members contributed 40 shillings initially, then 10 shillings annually, creating America's first subscription library. Franklin later reflected that this model "was the mother of all North American subscription libraries, now so numerous."

Franklin never heard of tax-exempt status or the term ‘nonprofit’ because, again, there was no federal income tax to be exempt from. He understood something more fundamental: purpose-driven organization are a technology for collective achievement capable of creating enormous value outside and beyond the pure drive for financial profit. The Library Company still operates today, nearly 300 years later, having outlasted countless for-profit enterprises from the same era.

Pennsylvania Hospital, also co-founded by Franklin in 1751, pioneered the matching grant—donors contributed, and the state legislature matched their contributions. This innovation in charitable financing became the template for modern philanthropy and government partnership models still used today.

When we think "501(c)(3)," we're thinking about tax policy. When Franklin thought about the Library Company and the Pennsylvania Hospital, he was thinking about organizational methodology—how to coordinate human effort around shared purpose rather than individual profit extraction.

Nonprofits are Overlooked in History

Most Americans assume profit-driven corporations built the institutions that define our nation. We hear about the great industrial barons like Andrew Carnegie (steel), Cornelius Vanderbilt (railroads and shipping), and John Rockefeller (oil). Without a doubt, these industries and the dominant corporations that drove them forward played a substantial role in the growth of the United States.

But it is inaccurate to overweight private sector contributions, especially at the founding of the republic. At that time, the first order of business was to establish the institutional precursors for subsequent American economic flourishing to take place.

The most recent Nobel Prize in Economics in 2024 was awarded to three prolific economists, Daron Acemoglu of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Simon Johnson at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and James A. Robinson at the University of Chicago, for their work to demonstrate with evidence, the foundational role strong, trustworthy, purpose-driven societal institutions play in unleashing economic prosperity in societies.

The Prize winners posit a substantial amount of the wealth inequity between nations today comes from the nature of their institutions, many of which were established during the period of European colonization, and was manifest differently according to the kinds of societies the colonists encountered in places they colonized.

Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson’s work describes a sharp contrast that develops over time depending on whether a country’s institutions are inclusive or extractive. Societies with inclusive (purpose-driven) institutions tend to develop into generally prosperous places, while those with extractive institutions become trapped persistent cycles of low economic growth.

This year’s laureates in the economic sciences – Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson and James Robinson – have demonstrated the importance of societal institutions for a country’s prosperity. Societies with a poor rule of law and institutions that exploit the population do not generate growth or change for the better. The laureates’ research helps us understand why.

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel 2024

The Founding Fathers understood the value of mission-driven organization intimately. When they crafted the Constitution, they embedded purpose-driven principles into the document itself. The Preamble doesn't promise profits to shareholders—it commits to "promote the general Welfare" and "secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity." The entire American experiment was, in essence, the world's most ambitious nonprofit startup.

These early institutions demonstrate something profound about organizational DNA. While profit-seeking enterprises are integral to wealth creation and catalyzing innovation, purpose-driven organizations are better suited to situations such as institution building wherein goals extend beyond quarterly returns, and the definition of success reaches far beyond net financial gain.

Franklin's various enterprises—the library, the hospital, the university, the postal service, the fire department—all operated on nonprofit principles decades before anyone conceived of shareholders demanding maximum returns. They solved community problems through collaborative resource pooling and shared governance.

Nonprofits are Not Helpless Charities

These days, one of our biggest obstacles to societal economic innovation is the fundamental misconception that treats nonprofits as charitable recipients rather than sophisticated businesses with inviolable missions. This charity illusion prevents us from recognizing nonprofits as competitive economic entities that happen to optimize for purpose instead of profit.

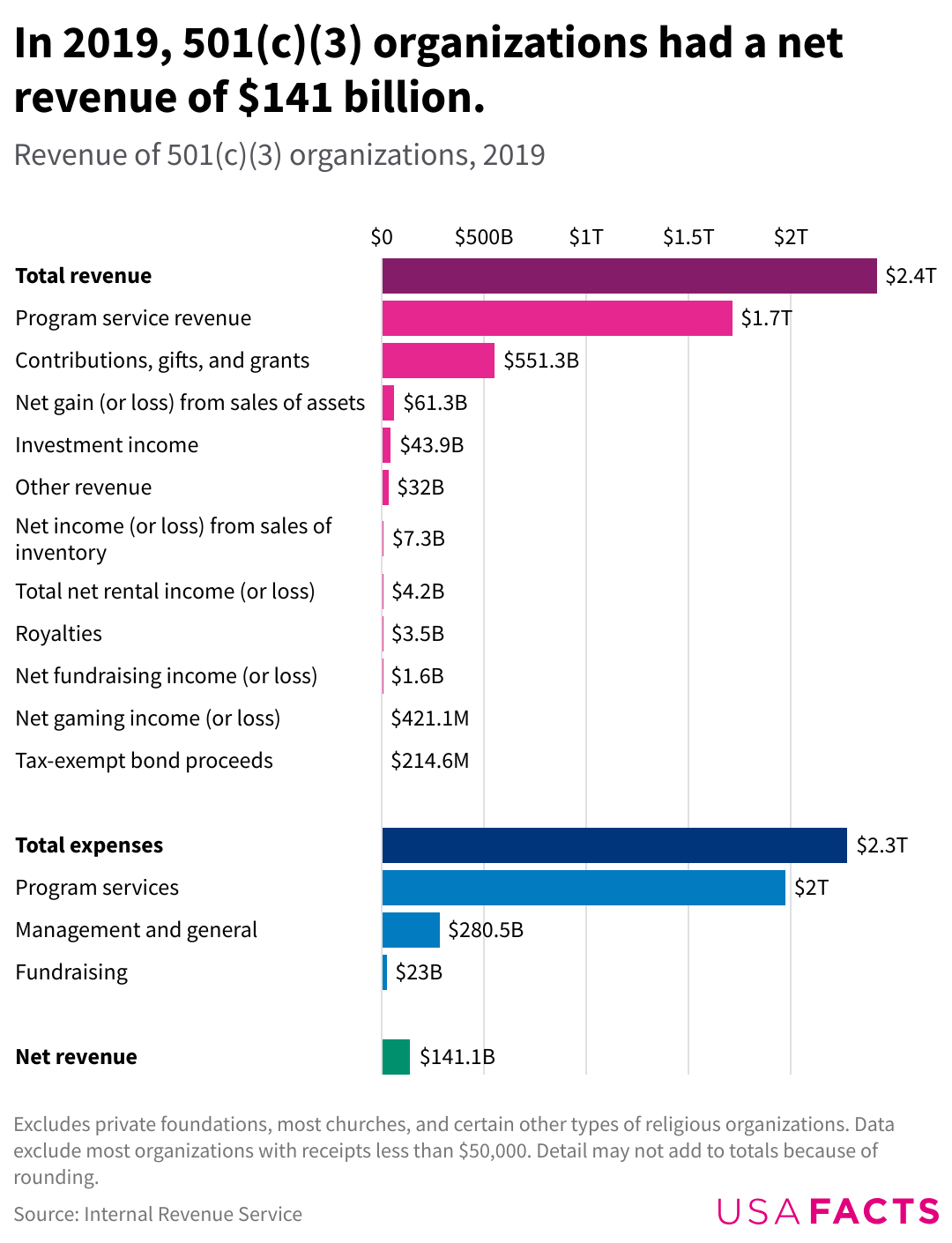

The numbers tell a different story than the dismissive charity narrative suggests:

Nonprofits by the numbers

$3.7 trillion in annual revenue - that's larger than the GDP of Germany

12.5 million employees - making nonprofits the third-largest employer in America

1.8 million organizations - more than a million more entities than all publicly traded companies combined

Here's the kicker: 70.8% of nonprofit revenue comes from fees for services, not donations.

These organizations operate sophisticated business models, generate substantial revenue, and compete effectively in marketplace conditions.

Consider REI Co-op, which generated $3.53 billion in revenue in 2024 while operating as a consumer cooperative focused on outdoor recreation access rather than shareholder returns. Or look at the stunning humanitarian and logistical achievement by World Central Kitchen, the nonprofit started by renowned Spanish chef, José Andrés, which earlier this year announced it had surpassed 500 million meals served since its founding in response to the devastating earthquake in Haiti in 2010.

The legal frameworks for this transformation already exist. Every local business—from bakeries to barbershops—could convert to nonprofit models while maintaining competitive service and creating community ownership rather than distant shareholder extraction.

Nonprofit organizational sophistication matters because we're approaching a moment when traditional profit incentives will eliminate most jobs. Communities need economic models that can coordinate human activity when pure financial rewards become scarce—exactly what nonprofits have perfected over centuries.

These aren't charity cases—they're examples of mission-driven organizations finding ways to operate creatively despite competing in a global economic system that is optimized for profit-maximizing entities. They are like organisms evolving new adaptive traits, finding ways to make purpose motivation into a competitive advantage.

Removing the distinction between "charitable cause" and "business with inviolable mission" reveals the organizational innovation nonprofits represent. They, like innovative for-profit startups, are solving fundamental challenges we all face, from providing consumers with the best outdoor recreational gear, to making sure people have shelter and enough food to eat.

The defining challenge of post-AI economics is: how to coordinate complex human activity when traditional profit incentives disappear.

Hospitals, universities, research institutes, disaster relief organizations—these nonprofits routinely coordinate thousands of workers, manage complex supply chains, and deploy resources across continents without relying on profit as the primary motivating force. They accomplish this through shared commitment to mission and sophisticated operational methodologies adapted specifically for purpose-driven environments.

This is exactly the organizational technology communities need to expand access to as AI eliminates profit-driven justifications for employment.

What All Three Misconceptions Hide

When you combine these three misconceptions, they create a dangerous blind spot: we can't see nonprofits as the sophisticated organizational alternative they represent for economic transformation.

The tax trap makes us think about regulatory compliance instead of operational methodology, as well as truncating the long history of purpose-driven entrepreneurship. This leads into the historical blind spot that makes us forget that purpose-driven organization built America's foundation. The charity illusion makes us think nonprofits need help rather than recognizing them as providers of solutions.

Together, these misconceptions prevent us from understanding that nonprofits have already solved the coordination challenges we'll face as AI reshapes the economy. They've developed organizational structures and operational methods specifically adapted to function when traditional market incentives don't apply.

While tech companies race to deploy AI as rapidly as possible and governments debate toothless regulations, nonprofits are quietly demonstrating that purpose-driven organization isn't just possible—it's proven, scalable, and more resilient than profit-maximizing alternatives.

We're in a narrow window where communities can still choose their economic destiny. Every month we delay building alternatives, AI systems become more capable and entrenched interests more powerful.

Nonprofits aren't preparation for the post-AI economy—they're proof it already works. The question isn't whether we can build a purpose-driven economy. The question is whether we'll act fast enough to build it before the choice is made for us.