#7 - Mistrust Is a Goldmine

The economic logic destroying our public square

Airports have always felt wondrous to me. The intricate choreography of tens of thousands of people merging their myriad and distant lives. Winding single file through roped queues, coffee lines, and security checkpoints, we are temporarily confined before human entropy propels us back out to all corners of the world.

Right now I hear murmurs in Mexican Spanish, parents cajoling a spiky-haired infant in Vietnamese, and energetic English inflected with Iowan friendliness at 4 in the morning. I see dusty cowboy boots, neon Nikes, chunky Doc Martins. Thick flannels, tourist t-shirts from the Florida Keys, Foxx Racing dirt bike racing tops, and dirty Carhartt pants. New York Yankees, San Diego Chargers, AC/DC, Ariat, BMW, USC—the baseball caps rep it all.

I’ll be forty years old in a few months, so I have about thirty years worth of airport memories to recall. I remember when my relatives were allowed to meet me at the gate in Sacramento, CA when I arrived to visit my grandparents in the years before 9/11. I remember when curbside checkin went away, when armrest ashtrays disappeared, when boarding passes started coming out of automated kiosks on receipt paper instead of glossy card stock, and when they became QR codes on our phones.

What hasn’t changed is my delight in witnessing, in joining this parade of everyday, real life humanity. Delays, stale air, and overpriced concessions aside, we come together around the miracle of flight and air travel.

One thing I haven’t mentioned about my present scene sitting here waiting for my flight at gate A2 in Des Moines International Airport is the omnipresence of screens in the hands of most of my fellow travelers. Our transfixion with smartphones is another thing that unites us.

To my right, a little boy no more than two years old is holding his father’s smartphone up to the face of his even younger sister in her baby carrier, and they are both captivated by the bright lights and colors on the screen.

In the wake of the violent murder of right wing influencer, Charlie Kirk, online discourse has erupted. A caustic brew of outrage, misinformation, and disinformation has spilled into the public square.

If you’re expecting my take on Kirk’s killing, my opinion of my opinion is that it doesn’t really matter and isn’t helpful to share.

What I wish to contribute is an observation—across all political persuasions, platforms and personalities, it has seemed to me that people are making a stronger and more immediate connection between our information ecosystem, our terminally online culture, and the sickness in our society. This is a very good sign.

Even more encouraging to me are the numerous diagnoses I’ve heard from pundits that trace the problem even more fundamentally to the economic incentives that stoke rage and hatred for clicks.

By now it is no secret that each of us receives an algorithmically curated stream of content fed to us through social media and our devices. Not only are we served different posts, memes, articles, videos, and news, but we may even see different headlines and thumbnail images that are optimized to capture our attention.

What is the magic ingredient that makes everything from reality TV shows, to sports, to soap operas, to political commentary so irresistible? Conflict.

Humans simply love a good battle. The tension, the drama, the suspense, victory and vanquishment, it’s all so deeply satisfying for the most primal parts of our nature.

Without conflict, all of humanity’s greatest stories from Genesis to Shakespeare to Star Wars would collapse from lack of narrative support. The scholar Joseph Campbell documented thousands of instances of what he called, the hero’s journey, a universal architecture people across time and cultures have used to make meaning from our lives, our struggles, our existence and human beings.

Like so many other resources, we have become monstrously efficient at sourcing, extracting, refining, and distributing conflict. But unlike substances we dig from the earth, we ourselves are the landscape being mined.

The algorithm monitors our every scroll, like, comment, and post with perfect machine vigilance scanning billions of feeds for signs of discord. Every tiny blip of potential friction gets tested and sorted up and up a chain of promulgation. An unkind word, a photo out of context, an AI generated fabrication—the competition for virality is Darwinian in its ruthlessness and ceaselessness.

The memes and takes that emerge victorious from the algorithmic gauntlet are apex specimens of rage bait, and they go on to reproduce even more formidable progeny by provoking even more intense responses.

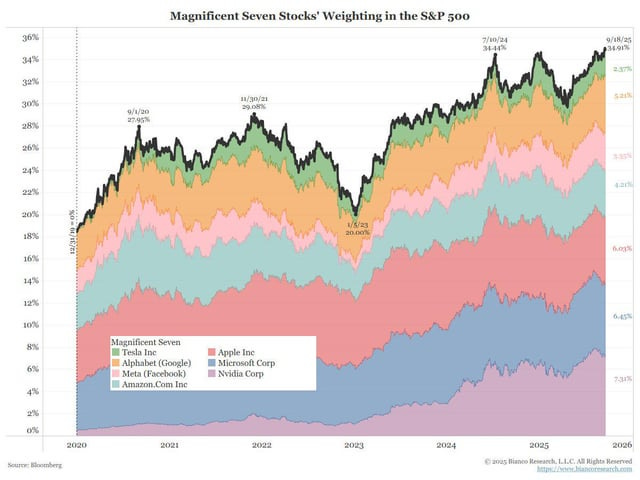

A small handful of companies own most of this modern conflict supply chain, and they use their ultra distilled product to capture our attention, which generates trillions of dollars of market value for them. Seven companies—Alphabet (Google), Meta (Facebook), Amazon, Apple, Microsoft, NVIDIA, and Tesla—are collectively referred to as the Magnificent Seven and they account for roughly 35% of the value of the S&P 500 index of leading global companies. This concentration of power is both impressive and deeply dangerous.

The absurdity of our predicament is obvious and has been for years. We have locked ourselves into an economic system that is built upon the stoking of our basest instincts for fear, conflict, and hatred. For us to win financially, we must lose socially, culturally, and spiritually.

Books and laws have been written to call attention to and address the problem, but none of it seems to be enough. The ideas in these books rely on the very machines they critique in order to spread, while the most effective online provocateurs have become the most powerful politicians in the world and do not want to dismantle the source of their power and influence.

In the immediate aftermath of Kirk’s killing, and in the midst of follow-on controversies such as the suspension of Jimmy Kimmel’s late night show at the behest of powerful media conglomerates and the FCC, most of the outcry has been directed at specific corporate and political leaders.

This is where punditry is largely falling short of calling for the most effective course of corrective action by falling into the original trap of character-driven outrage. For all of their power, these leaders actually have very few real choices before them. In reality, the CEOs of even the most powerful private companies have a severely restricted range of motion which includes only actions that serve to benefit shareholder value.

I’m not trying to absolve people of individual responsibility. I hope executives like Disney CEO, Bob Iger know they are in the wrong. Despite being among society’s best equipped to take a stand, they are nevertheless aiding the destruction of important institutions and values. They are passing on the rare chance to earn a public legacy of courage.

But if it wasn’t Bob, it would be someone else. We’ve seen law firms, elite universities, tech companies, and media conglomerates, a who’s who of society’s most wealthy and powerful corporations, all cave to implicit financial threats. As organizations they are behaving rationally, in accordance with what their reptilian corporate nervous systems tell them to do—seek revenue, avoid cost, promote shareholder value. This is the extent of the “choices” available to them.

The seemingly frantic motions of the ABC parent company, Disney removing Kimmel and then reinstating him last night after a week hiatus, might look like chaos or cowardice, but it is, in fact, the perfectly rational response of a base corporate organism responding to perceived threats.

First, its profits were threatened by major local news giants Nexstar and Sinclair under pressure from the Trump Administration, so the company moved to appease them. That triggered a response from Hollywood elites and Disney customers who threatened boycott Disney productions and products. Like a snake parrying to avoid a stick being waved at it side to side, the company pivoted to reinstall Kimmel.

This is the trap we have locked ourselves into. Our leaders, both corporate and political, are behaving extremely rationally from the perspective of profit seeking. We have conflated the cornucopia of consumer choice and bargain prices created by 50 years of profit-maximalist economic dogma with the actual human freedom to choose. We are being shown, in real time, how much of our human agency has been subordinated by our modern economic apparatus.

The most serious threat to our freedoms is not a thin-skinned autocrat, but our collective prostration under the yoke of profit hyper-dominance. We have allowed the market to colonize not just our economy, but our public square, and trust, itself.

Trust, it turns out, is terrible for business. When neighbors believe their neighbors, when citizens trust their institutions, when communities rely on shared values—none of this generates clicks, engagement, or revenue. But mistrust? Mistrust is a goldmine. Every broken relationship creates a market opportunity. Every eroded institution opens space for a profitable replacement. Every fractured community becomes a target demographic.

This is why our information ecosystem feels deliberately designed to make us suspicious of each other. Because it is. The same profit logic that gave us miraculous flight and global connectivity has now turned its algorithmic attention to our most fundamental social bonds. Trust is free—and therefore worthless to a system that can only see value in transactions.

In a few minutes, I’ll board my flight along with my fellow travelers, whisked through the atmosphere at 500 mph in a climate-controlled miracle complete with snacks and entertainment. But I’ll also be surrounded by people increasingly unable to agree on basic facts about the world we share, each of us fed different versions of reality optimized for our individual engagement.

We’ve built a system so efficient at extracting value that it has begun strip-mining the social fabric itself. The profit motive isn’t evil—it’s just indiscriminate. It will monetize anything, including the very trust and shared reality that functional societies require.

Until we recognize that some things must remain outside the market—justice, truth, community bonds—we will continue watching our public square dissolve into a collection of profitable conflict zones. The choice isn’t between capitalism and something else. It’s between a system that serves human flourishing and one that simply serves itself.